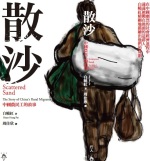

Scattered Sand:

The Story of China's Rural Migrants

First-hand report on the largest migration in human history

Each year, 200 million workers from China's vast rural interior travel between cities and provinces in search of employment: the largest human migration in history. This indispensable army of labour accounts for half of China's GDP, but is an unorganized workforce-'scattered sand', in Chinese parlance-and the most marginalized and impoverished group of workers in the country. For two years, Hsiao-Hung Pai travelled across China, visiting migrant workers in labour markets and work sites in the northeast and central China, in the coal mines and brick kilns of the Yellow River region, and at the factories of the Pearl River Delta. Scattered Sand is the result of her travels: a finely wrought portrait of those left behind by China's dramatic social and economic advances.

Foreword by Gregor Benton

Published by Verso, 2012

Scattered Sand has won the Bread and Roses Award for Radical Publishing

Guest judge Nina Power said the title presented a "vivid, intimate and highly-engaging picture of work in contemporary China". She added: "Pai's book evidences compassion and passion in equal measure for the workers she talks to, and presents a highly convincing, if often depressing, portrait of rural to urban migration and economic exploitation."

Endorsement

"Hsiao-Hung Pai's intrepid journalism is one of the most revealing guides to contemporary China."

- Pankaj Mishra, author of From the Ruins of Empire

"Scattered Sand captures the sadness, resilience and anger of China's millions of internal and international migrants. This illuminating book effortlessly interweaves individual voices, rarely heard by English-speaking audiences, with the history, politics and economics that shape migrants' stories and their choices."

- Bridget Anderson, author of Doing the Dirty Work: The Global Politics of Domestic Labor

Reviews

The Observer

by Sukhdev Sandhu

The lives of China's rural migrants come into sharp focus in this insightful account

"A worthy successor to A Seventh Man"

Back in 1975, John Berger and the Swiss photographer Jean Mohr produced an unusual book entitled A Seventh Man about the millions of rural migrants moving to western Europe to perform menial industrial labour. It fused poetic text, political analysis and striking images - one depicted a solitary figure on a horse and cart, having just left behind his ancestral land, slowly wending through sun-blazed dusty lanes in pursuit of a new life - in order to ask why those migrant workers are "treated like replaceable parts of a machine? What compels them to leave their villages and accept this humiliation?"

The images in Taiwan-born, British-based journalist Hsiao-Hung Pai's Scattered Sand are descriptive rather than photographic, but in every other way her book is a worthy successor to A Seventh Man. It focuses on contemporary China, where the scale of rural migration - over 130 million men and women have left their home provinces in search of work - makes the demographic debates about modern-day Europe seem parochial and hysterical. It pays tribute to a class of people that, although exalted under Mao as a revolutionary vanguard, has constantly to face the threat of pauperisation. It amplifies sounds - plaintive chants, desperate petitions, exhausted prayers, sceptical curses - that are often drowned out by the stentorian boosterism of the state loudspeaker.

Scattered Sand (its name comes from a dismissive term given to unorganised rural migrants) can be seen as an anthology of ghost stories. Its subjects, compelled to move by stagnant local economies and corrupt officials flogging off land to corporations, are invisible to many Chinese urban dwellers who have no interest in learning about the crowded shacks or cheap hostels into which they squeeze. In Fujian province Pai learns of men who toil in unsafe mines for the equivalent of 18 pence a day, risking lung diseases for which they can't be compensated because they lack work contracts.

And yet, what makes this book so important is that Pai rejects the all too common and deeply sinophobic assumption that China can only be described in quantum terms. It's commonly portrayed as too big, its recent transformations too vast to grasp, its population a muted and faceless army of drone labour. Pai, by contrast, treks to building sites few outsiders visit, wanders down side alleys to talk to the poor and the crooked, keeps in touch with her confidantes by letter and by phone over a number of years.

From these intimacies she shows her subjects not as ghosts, but as decent, quietly heroic men and women who sacrifice blood, sweat and tears to support their families. Literally so: in the "plasma economy" of Henan, a province full of underground blood clinics, she meets a peasant who sells his blood up to three times a day, in part to pay off a fine for having more than one child.

Injustices and indignities scream out of every page. Starting out in Moscow where around 50,000 migrants eke out livings in the face of skinhead violence, Pai moves across China - the brick kilns of the Yellow river region where child labourers are common, Sichuan where years after the 2008 earthquake millions live in temporary housing, the troubled region of Xinjiang in which anti-Muslim sentiment is rife - to present stories that run counter to the triumphalism of politicians, starchitects and speculators.

The book shines an uncomfortable spotlight on Britain too. After all, it's our desire for cheap toys and clothes to which many Chinese factories cater. It's our fondness for the freedom and mobility promised by laptop computers that fuels the profits of companies such as Foxconn at whose factories nets have been installed to stop workers jumping to their deaths. Are our labour laws perfect? A heartbreaking chapter in which Pai meets relatives of one of the cockle pickers drowned at Morecambe Bay in 2004 suggests not. Scattered Sand does well to draw attention to the ways in which millions of Chinese people, in the face of physical threats and a censorious press, have gone on strikes and marches to protest against their conditions. Classic labour texts - A Seventh Man, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men - often privilege exploitation over resistance. Pai, diligent to the end, and writing out of love rather than hatred for China, holds on to the hope that resistance is fertile.

Literary Review

by Jonathan Mirsky

Next time you buy something in Primark spare a thought for the Chinese human being who made that dirt-cheap item. I say dirt-cheap advisedly because the employer almost certainly treated the maker like dirt. Not long ago a friend said she feared that China was" going to take over the world." She mentioned China's enormous Gross National Product. But getting on for half that enormous sum is generated by rural people who left their ever-poorer villages to hunt for work, badly paid and unremitting, in the parts of cities tourists never see. Then there are the tens of thousands of once-rural Chinese living in the UK illegally, who do jobs scorned by Poles and Ukrainians.

All this is laid bare by the incomparable and eloquent Hsiao-hung Pai, a Taiwanese woman whose excellent previous book, "Chinese Whispers", focused first on the Chinese cockle-pickers doomed to drown in Morecambe Bay in 2004 by heartless Chinese and British "gang masters". She then explored more widely the plight of Chinese immigrants here.

Now Ms Pai - will she ever get another Chinese visa? - spent two years in China examining the lives and fortunes of the 200 million rural people who left their homes, like "scattered sand," to work elsewhere, either in China or abroad. There are earlier books on this subject, notably Leslie T.Chang's "Factory Girls," and Alexandra Harney's "The China Price," but they do not match Ms.Pai's scope, analysis, information and occasional rage.

What she accomplishes is that difficult thing, deftly combining personal testimony with statistics. One never wonders, after some particularly ghastly first-person observation, whether this is too awful to be generally true.

Take, for example, the grim fact that many migrants are reduced to repeatedly selling their blood, at dire risk of contracting AIDs from unsterilized needles. Ms Pai tells us about Qi Cheng, who beginning at the age of sixteen "sold his blood a thousand times - literally. Sometimes he sold 700 to 800 centilitres three times a day,"[99] all over Henan, his native province. He made enough money to buy three houses, but after fifteen years he and his wife died of AIDs, leaving four children. Ms Pai interviewed Dr Gao Yaojie, a gynecologist and AIDs specialist, who met Qi in the course of visiting one hundred villages, and warned the public about the misery of thousands of AIDs sufferers and belabored the government's corruption and incompetence. Like many Chinese whistle blowers she was persecuted, in her case for of "damaging Henan's reputation," [102] and driven abroad.

A typically masterful coordination of personal and national occurs when Ms Pai meets some survivors of the terrible Sichuan earthquake of 2008; no one had received any of the promised government compensation. An elderly white-haired man suddenly speaks. "We peasants brought the Party to power. But once they came to power we became burdened and exploited again.... And do you know what we peasants had as our reward in the decades that followed the Revolution?" The crowd was rapt. " Poverty! That's the principle upheld by our great leaders."[57]

One of Ms Pai's unique strengths, nearly impossible for even the most experienced foreign correspondent, is making friends with the people she meets, sharing meals and chats, and feeling despair at some of their testimonies. In Beijing she meets Xuan, from a village with only a few hundred inhabitants. He says to her, " Do you know what democracy means in China? It means good connections. ...If you have good connections, you can buy your status." [221] Xuan migrated to Beijing where he sweated seven days a week for a security company. Wages were pitiful, with no sick pay or holiday paid leave. Always paid a month behind, it was impossible for him to leave for something better. Ms.Pai takes Xuan to Tiananmen Square where after six years in the capital he had never been. (She makes a common error; Mao did not proclaim, "The Chinese people have stood up" in Tiananmen Square.) Gazing at the tanks and floats on display, Xuan is aghast. "How much those in power care about face...Their face is much more important and expensive than our bare bottoms."[226]

Ms. Pai's book is just right for anyone even slightly interested in China and worried about this becoming the Chinese century; and it may jolt academic specialists clinging to the conviction that the Chinese "economic miracle" is widespread. The "reality," Hsiao-hung Pai states, " is that China has been struck hard by the global recession and is as bitterly divided as the rest of the world...[11] 'socialism with Chinese characteristics' reveals itself to be little more than a variant of the brutal capitalist order that the Communists once denounced..."[13]...

Wall Street Journal

by Frank Dikötter

"We hear a lot about cheap products made in China, but how about the 200 million migrants who leave the impoverished countryside every year in search of work? Pai Hsiao-hung spent two years examining the lives of laborers in coalmines, brick kilns and factories across the country. They are dirt poor and treated like untouchables, barely able to survive on pitiful wages. Pai's book is exceptional not only in the depth of her research, but also in giving a voice to the people she befriends. Essential to understand the human reality behind China's so-called economic miracle."

New Statesman review

by Isabel Hilton

The Independent review

by Rachel Halliburton

The painstaking journalism here offers remarkable insights into the plight of China's new citizens

Daily Beast review

by Ross Perlin, author of Intern Nation

Ghosts in the machine: the story of China's rural migrants and their uncertain future

Behind the economic miracle of China stands millions of rural migrants who keep the country going. Ross Perlin on a new book that tells their stories-and wonders what happens if China stops growing.

Every year, the awkwardly named Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development, an arm of the powerful State Council, announces the list of China's 592 "Poverty Counties." All of them are rural, and most are in the country's underdeveloped west: mountainous, off the grid, populated by non-Han ethnic minorities. The typical resident is a small-time farmer tilling a few acres of exhausted soil, one of 128 million rural Chinese living on less than a dollar a day.

To visit such places, as few travelers ever do, is to peel back layer after layer of development, returning to an older China of Mao suits, subsistence agriculture, and single-lineage villages. You begin in the provincial capital, always the wealthiest and most developed city. Next stop, after a long journey by bus, is the capital of the prefecture (a level of government with no U.S. equivalent): here global brands, white-collar workers, and high-tech gadgets are already much less in evidence. Then the xiancheng, or "county seat," significantly smaller but with its markets, schools, and hospitals still powerful magnets for the surrounding countryside. Only then do you come to the villages. Basic services and facilities are now hard to come by; roads may be unpaved or nonexistent; children and old folks predominate. A palpable desolation-and the feeling of what the Chinese call luohou, or backwardness-hangs in the air.

China's migrant workers, desperate to escape these conditions, are traveling in precisely the opposite direction. Over the past three decades, some 200 million of them have left home to find work, two thirds going beyond their home provinces and millions overseas undertaking what is justifiably called the largest migration in human history. As Taiwanese journalist Hsiao-Hung Pai persuasively demonstrates in Scattered Sand, many members of this "new mobile proletariat," despite 80-hour work weeks and backbreaking labor, are becoming virtual untouchables, caught between a blighted countryside and hostile, unattainable cities. Despite powering the country's economic growth, they receive a pittance of the proceeds. The number of "mass incidents," many the work of migrants, grows by the year. The "floating population" (liudong renkou in Chinese) is the specter haunting China.

Previous accounts, such as Leslie Chang's Factory Girls (2008) and Michelle Loyalka's Eating Bitterness, released earlier this year, have elucidated the human stories without providing a systematic account. Apologists have emphasized tales of success and empowerment while critics have focused on poor working conditions at just a handful of high-profile, multinational factories (last month's Foxconn riot being a case in point). Pai, whose 2008 Chinese Whispers exposed migrant labor in the U.K., spent two years earning migrants' trust in factories, train stations, and worker housing complexes across the country. Eloquent and wide-ranging, Scattered Sand not only does justice, eloquently and comprehensively, to their increasingly marginal position in Chinese society, it also provides useful whirlwind introductions to Chinese labor policy, local government corruption, and minority discrimination, among other issues.

Although mostly focused on the domestic, Pai also reveals Chinese migration patterns to be fiendishly complicated and global in reach. She meets some of the estimated 50,000 Chinese small traders at the Cherkizovsky Market in Moscow, selling counterfeit goods out of wooden shacks until their expulsion by Russian authorities. In one of the book's most poignant sections, she interviews relatives of the 21 Chinese cockle pickers who drowned in 2004 at Morecambe Bay, northwest England. She describes the epic ordeals of Fujianese migrants, dissatisfied with domestic opportunities, who pay "snakeheads" upward of $30,000 to be smuggled into Western Europe at grave personal risk.

Pai is closely attuned to particularities and details that may matter greatly within China but are little understood outside. She scrupulously records how migrants from particular villages, counties, and provinces tend to cluster in often unpredictable destinations. (Sichuanese migrants are an exception, famously being found everywhere and doing every kind of work). She notices the variety of occupations undertaken by migrants, visiting several "labor markets," vast and chaotic hiring halls that have no real American parallel. Light and heavy industry, mining, construction, and security are among the industries that rely most on migrants, but there is also sex work, restaurant work, low-level white collar labor, driving motorbike-taxis, cleaning, caregiving, domestic work, and so on.

Given the immensity of China's rural-urban divide, even domestic migration represents a much greater step than simply picking up and moving. The anachronistic hukou (household registration) system continues to tie all Chinese citizens to an original laojia (hometown), making it difficult for rural migrants to access basic services like health care and education elsewhere. While Chinese cities are largely free of shantytowns and favelas, migrants often live in squalid, remote "man camps," effectively trapped by their employers. Wage theft and worker abuse are commonplace, labor laws are ignored, minimum wage increases trail inflation, and the country's one official labor union remains a toothless bureaucracy, beholden only to the state and to employers. On the streets of any Chinese city, tattered or dusty clothes, bronzed skin, rustic manners, and "nonstandard" accents render migrants a caste readily identified and easily exploited.

Yet whatever "bitterness" migrants have to "eat," they can hardly stay on the farm, as Pai and just about every other observer agree. Demographic and environmental pressures have made rural life unsupportable, especially in contrast to the new prosperity in the cities, which government policy has consistently favored for the past 20 years. Disassembling the previous system of collectives and communes, Deng Xiaoping's reforms left most peasants with tiny holdings, often too measly for basic subsistence, and paved the way to an enclosure movement led by corrupt local governments. Pai records this dark assessment from one old man, despairingly hanging around a labor market with his unemployed son: "China's history is all about how the peasantry has been burdened and oppressed, and how each time they rose up to overthrow those in power."

The immediate catalyst for departure, however, is usually the success stories of a fellow villager. The rural economy may be a dead end, but some of these migrants ply their savings into massive new compounds back in the laojia. In rural Henan, Pai meets the coal dealer Da Cai, one of five brothers, all but the youngest of whom left their native village. After years spent mining coal and driving a cab in a coastal city, he has squeezed his way into the middle class by going into business for himself. In the megacity of Guangzhou, a female factory worker named Ying puts her career above her marriage, takes wage cuts without complaint, steers clear of "those with attitudes" (i.e. strikers), and is eventually promoted to a quasi-white collar position in the product control department, earning up to 1800 RMB ($285) per month. Call it the Chinese Dream. As long as the economic engine keeps chugging, people like Da Cai and Ying-or at least their children-feel they have a reasonable shot at joining the urban middle class, or potentially even vaulting into the managerial, bureaucratic, or entrepreneurial classes where power and wealth are increasingly concentrated.

Yet for every Ying and every Da Cai, there are many migrants who never make it, who move from one precarious job to the next or eventually move back to the village in frustration, minus the compound. For the time being, "inner-city poverty" still sounds like a contradiction in terms to the Chinese ear. The effects of a serious economic slowdown remain unknowable. The number of mass incidents increases each year. Pai is silent on what will become of rural China, where 650 million people still live, agribusiness remains rare, and poverty alleviation efforts are ongoing, recently strengthened under the banner of the "New Socialist Countryside." "Harmonious development" has been the favorite slogan of China's outgoing rulers, who just handed over power at the 18th Party Congress. No one knows what the next slogan will be.

Interview with Ryan Wong, for The Margins (US)

Red Pepper review

BBC Mundo interview

Review by Delia Davin, The China Quarterly, Cambridge University Press

The Chinese edition of Scattered Sand has been published by 行人出版社 in June 2014, in Taipei.